Getting in “hot deals” can be tougher than you think

Managers (“VCs”) know from experience that getting into a ‘hot’ deal can be a tough challenge. And that it is not enough to source the deal, go through the necessary due diligence and have an internal investment committee approve the investment. In many cases, this leads to the deal being lost.

Contrary to the common belief that startups constantly need funding and must do all in their power to please venture capitalists, the ‘hyped’ or ‘high potential’ companies in many cases do not get chosen, rather are given the ability to choose, with some going as far as to leave special, small, allocations in a funding round for their inner network, a sort of ‘friends and family’ bucket. These highly skilled founders are capable of raising massive amounts of capital at hundreds of dollar valuations regardless of how far along the company is, in many cases without a single dollar in revenue or even a product, further contributing to the notion that the decision to invest is not always in the fund managers’ hands. Just a few months back I heard of a company in the Bay Area valued at over 50 million dollars without so much as a website, followed by tales of people applying for job positions not knowing what the business was or what their position would be. This was a company not actively looking for investors and declining offers from top tier venture capitalists.

…

As the venture capital ecosystem matured over the years, so did startups and their founders. Despite a proliferation of ‘good’ startups and a growing investment opportunity set, managers were forced to re-evaluate their roles as investors in a company — this is particularly true for the early-stage space (Seed and Series A) — with many of them focusing on new and different ways they can truly add value to their portfolio companies.

This new paradigm also has its fair share of implications for portfolio construction, as it is something managers cannot neglect when defining their overall strategy and assessing how many companies they can give the necessary support, i.e. optimal portfolio size. But that’s a whole new — and very long… — discussion. (Look out for my upcoming article “The 2-Sides of the Power Law”)

Boosted by the colossal growth rates technological developments have enabled, fast-growing startups have different needs now. Forcing managers to dedicate a great deal of time to understand how they can best help companies scale their business, teams, or operations in a sustainable, efficient way.

Different startups at different stages of development, e.g. Seed vs Series D, have different needs. While an early-stage company might need more help in setting up its operation, developing its technological stack, or being introduced to other VCs; a later stage company might be more focused on growing its team or expanding to new geographies. In the face of these ever-changing needs, managers need to adjust to the needs of each of their founders.

The degree to which managers get involved varies significantly from firm to firm, with some giving an almost incubator like support, offering in many cases a team of in-house operating professionals which founders can rely on to help with shortcomings in specific functional areas; and others taking a more direct approach on a company-by-company basis, with managers assisting directly with specific issues, e.g. scouting and helping with the hire of senior executives or providing access to a network founders can leverage when necessary.

…

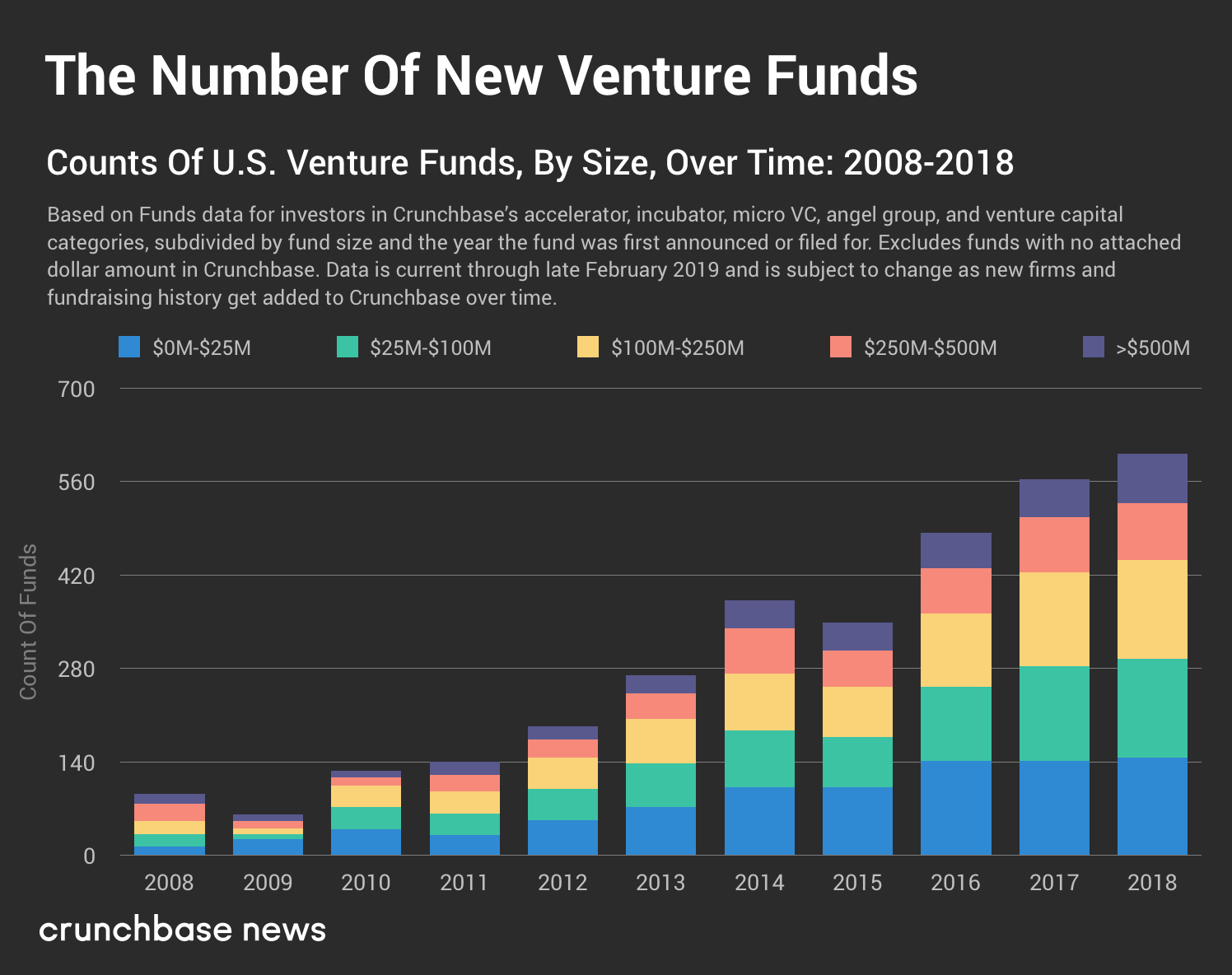

The time has passed when venture firms could compete on capital alone. From the turn of the millennia, the number of VC funds have been increasing at a galloping rate across the globe, with a whopping $254billion being invested in 2018 alone, a 46% increase from 2017 figures. Also, CrunchBase data shows that the pace at which new funds are being raised has increased sixfold over the past 10 years, with sub-$100m venture funds accounting for approximately 50 to 60% of all new funds announced by US firms. (Figure 1)

The same way the success of many emerging startups is to some extent linked to the rate at which founders spin out of big successful technology companies; developments in the venture industry are also often driven by principals or partners from top tier venture capital firms who decide to raise their own funds. This growing number of new, smaller, venture funds tend to focus in early-stage rather than late-stage, with many managers choosing to spin out to new projects out of a genuine passion for the Pre-seed, Seed, and Series A space. Furthermore, research from Cambridge Associates shows that from 2002 to 2012, emerging managers were responsible for between 40 to 70% of total gains in the industry, restating the idea that small funds outperform.

These emerging managers strive to build long-lasting platforms and address specific market opportunities, by taking advantage of their network with young founders. Some of these newly created funds are highly specialized, focusing on sub-sectors, such as RPA (Robotic Process Automation) or IaC (Infrastructure as Code); on specific geographies, like the UK or Israel; or in certain stages, e.g. Seed. This sharper focus and know-how on a specific topic enables emerging managers to provide in-depth targeted support to founders and level the field in an increasingly competitive market, with some of these emerging managers having been face to face with heavyweights such as Index, Accel and the like. And won.

During a fund’s AGM (Annual General Meeting) it is not uncommon to have some of the portfolio companies go on stage and pitch to the fund’s LPs. This is how managers engage with their own investors and showcase some of the ‘stars’ in their portfolio. Nevertheless, there seems to be a certain trend in the final remarks of startups in the portfolio of emerging managers. Rather than addressing investors directly, and making way for a potential future funding round, founders spend these final remarks highlighting how much managers have helped them along the way, from legally registering the company, to helping to raise subsequent funding rounds, with some going as far as to show screenshots of talks they have had with the managers, at all sorts of times and about a vast array of topics.

All in all, an increasing number of founders is discovering that for the first stages of a company, having a dedicated manager, with a more concentrated portfolio by their side can prove to be a far better choice than a big “franchise fund”. In an industry that is in continuous change, managers cannot neglect founders’ interests and need to remember that they too are being assessed and dependent on proving they can add value to the company. And founders must keep in mind not to look out for an investor, but rather for a long-term partner.